77 Personality and the Psychodynamic Perspective

What is Personality?

Personality refers to the long-standing traits and patterns that consistently propel individuals to think, feel, and behave in specific ways. Our personality is what makes us unique individuals. Each person has an idiosyncratic pattern of enduring, long-term characteristics and how they interact with others and the world around them. Our personalities are thought to be long-term, stable, and not easily changed. The word personality comes from the Latin word persona. In the ancient world, a persona was a mask worn by an actor. While we tend to think of a mask as being worn to conceal one’s identity, the theatrical mask was originally used to either represent or project a specific personality trait of a character (Figure 1).

Historical Perspectives

The concept of personality has been studied for at least 2,000 years, beginning with Hippocrates in 370 BCE (Fazeli, 2012). Hippocrates theorized that personality traits and human behaviors are based on four separate temperaments associated with four fluids (“humors”) of the body: choleric temperament (yellow bile from the liver), melancholic temperament (black bile from the kidneys), sanguine temperament (red blood from the heart), and phlegmatic temperament (white phlegm from the lungs) (Clark & Watson, 2008; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985; Lecci & Magnavita, 2013; Noga, 2007). Centuries later, the influential Greek physician and philosopher Galen built on Hippocrates’s theory, suggesting that both diseases and personality differences could be explained by imbalances in the humors and that each person exhibits one of the four temperaments. For example, the choleric person is passionate, ambitious, and bold; the melancholic person is reserved, anxious, and unhappy; the sanguine person is joyful, eager, and optimistic; and the phlegmatic person is calm, reliable, and thoughtful (Clark & Watson, 2008; Stelmack & Stalikas, 1991). Galen’s theory was prevalent for over 1,000 years and continued to be popular through the Middle Ages.

In 1780, Franz Gall, a German physician, proposed that the distances between bumps on the skull reveal a person’s personality traits, character, and mental abilities (Figure 2). According to Gall, measuring these distances revealed the sizes of the brain areas underneath, providing information that could be used to determine whether a person was friendly, prideful, murderous, kind, good with languages, and so on. Initially, phrenology was very popular; however, it was soon discredited for lack of empirical support and has long been relegated to the status of pseudoscience (Fancher, 1979).

In the centuries after Galen, other researchers contributed to the development of his four primary temperament types, most prominently Immanuel Kant (in the 18th century) and psychologist Wilhelm Wundt (in the 19th century) (Eysenck, 2009; Stelmack & Stalikas, 1991; Wundt, 1874/1886) (Figure 3). Kant agreed with Galen that everyone could be sorted into one of the four temperaments and that there was no overlap between the four categories (Eysenck, 2009). He developed a list of traits that could be used to describe a person’s personality from each of the four temperaments. However, Wundt suggested that a better personality description could be achieved using two major axes: emotional/nonemotional and changeable/unchangeable. The first axis separated strong from weak emotions (the melancholic and choleric temperaments from the phlegmatic and sanguine). The second axis divided the changeable temperaments (choleric and sanguine) from the unchangeable ones (melancholic and phlegmatic) (Eysenck, 2009).

Sigmund Freud’s psychodynamic perspective of personality was the first comprehensive theory of personality, explaining a wide variety of both normal and abnormal behaviors. According to Freud, unconscious drives influenced by sex and aggression, along with childhood sexuality, are the forces that influence our personality. Freud attracted many followers who modified his ideas to create new theories about personality. These theorists, referred to as neo-Freudians, generally agreed with Freud that childhood experiences matter, but they reduced the emphasis on sex and focused more on the social environment and effects of culture on personality. The perspective of personality proposed by Freud and his followers was the dominant theory of personality for the first half of the 20th century.

Other major theories emerged, including the learning, humanistic, biological, evolutionary, trait, and cultural perspectives. In this chapter, we will explore these various perspectives on personality in depth.

Think It Over

- How would you describe your own personality? Do you think that friends and family would describe you in much the same way? Why or why not?

- How would you describe your personality in an online dating profile?

- What are some of your positive and negative personality qualities? How do you think these qualities will affect your choice of career?

Freud and the Psychodynamic Perspective

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) is probably the most controversial and misunderstood psychological theorist. When reading Freud’s theories, it is important to remember that he was a medical doctor, not a psychologist. There was no such thing as a degree in psychology when he received his education, which can help us understand some of the controversy over his theories today. However, Freud was the first to systematically study and theorize the workings of the unconscious mind in the manner we associate with modern psychology.

In his early career, Freud worked with a Viennese physician Josef Breuer. During this time, Freud became intrigued by the story of one of Breuer’s patients, Bertha Pappenheim, who was referred to by the pseudonym Anna O. (Launer, 2005). Anna O. had been caring for her dying father when she began to experience symptoms such as partial paralysis, headaches, blurred vision, amnesia, and hallucinations (Launer, 2005). In Freud’s day, these symptoms were commonly referred to as hysteria. Anna O. turned to Breuer for help. He spent 2 years (1880–1882) treating Anna O. and discovered that allowing her to talk about her experiences seemed to relieve her symptoms. Anna O. called his treatment the “talking cure” (Launer, 2005). Although Freud never met Anna O., her story served as the basis for the 1895 book Studies on Hysteria, which he co-authored with Breuer. Based on Breuer’s description of Anna O.’s treatment, Freud concluded that hysteria was the result of sexual abuse in childhood and that these traumatic experiences had been hidden from consciousness. Breuer disagreed with Freud, which soon ended their work together. However, Freud continued to work to refine talk therapy and build his theory on personality.

Levels of Consciousness

To explain the concept of conscious versus unconscious experience, Freud compared the mind to an iceberg (Figure 4). He said that only about one-tenth of our mind is conscious, and the rest of our mind is unconscious. Our unconscious refers to that mental activity we are unaware of and cannot access (Freud, 1923). According to Freud, unacceptable urges and desires are kept in our unconscious through a process called repression. For example, we sometimes say things we don’t intend to say by unintentionally substituting another word for the one we meant. You’ve probably heard of a Freudian slip, the term used to describe this. Freud suggested that slips of the tongue are actually sexual or aggressive urges, accidentally slipping out of our unconscious. Speech errors such as this are quite common. Seeing them as a reflection of unconscious desires, linguists today have found that slips of the tongue tend to occur when we are tired, nervous, or not at our optimal level of cognitive functioning (Motley, 2002).

According to Freud, our personality develops from a conflict between two forces: our biological aggressive and pleasure-seeking drives versus our internal (socialized) control over these drives. Our personality results from our efforts to balance these two competing forces. Freud suggested we can understand this by imagining three interacting systems within our minds. He called them the id, ego, and superego (Figure 5).

The unconscious id contains our most primitive drives or urges and is present from birth. It directs impulses for hunger, thirst, and sex. Freud believed that the id operates on the “pleasure principle,” in which the id seeks immediate gratification. Through social interactions with parents and others in a child’s environment, the ego and superego develop to help control the id. The superego develops as a child interacts with others, learning the social rules for right and wrong. The superego acts as our conscience; our moral compass tells us how we should behave. It strives for perfection and judges our behavior, leading to feelings of pride or—when we fall short of the ideal—feelings of guilt. In contrast to the instinctual id and the rule-based superego, the ego is the rational part of our personality. It’s what Freud considered to be the self, and it is the part of our personality seen by others. Its job is to balance the demands of the id and superego in the context of reality; thus, it operates on what Freud called the “reality principle.” The ego helps the id realistically satisfy its desires.

Video 1. Psychoanalytic Theory explained.

The id and superego are in constant conflict because the id wants instant gratification regardless of the consequences, but the superego tells us that we must behave in socially acceptable ways. Thus, the ego’s job is to find the middle ground. It helps satisfy the id’s desires in a rational way that will not lead us to feelings of guilt. According to Freud, a person with a strong ego, which can balance the demands of the id and the superego, has a healthy personality. Freud maintained that imbalances in the system can lead to neurosis (a tendency to experience negative emotions), anxiety disorders, or unhealthy behaviors. For example, a person dominated by their id might be narcissistic and impulsive. A person with a dominant superego might be controlled by feelings of guilt and deny themselves even socially acceptable pleasures; conversely, if the superego is weak or absent, a person might become a psychopath. An overly dominant superego might be seen in an over-controlled individual whose rational grasp on reality is so strong that they are unaware of their emotional needs or in a neurotic who is overly defensive (overusing ego defense mechanisms).

Defense Mechanisms

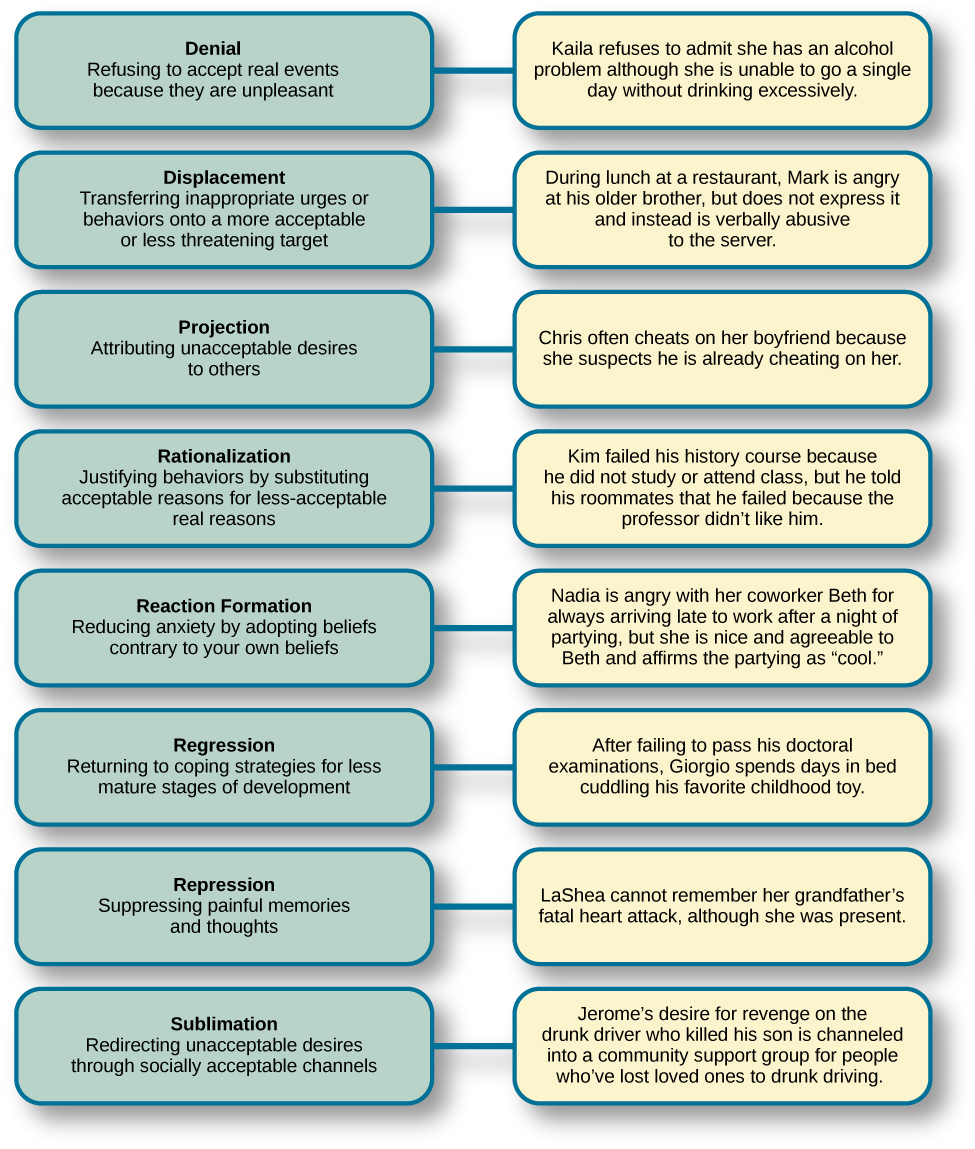

Freud believed that feelings of anxiety result from the ego’s inability to mediate the conflict between the id and superego. When this happens, Freud believed that the ego seeks to restore balance through various protective measures known as defense mechanisms (Figure 6). When certain events, feelings, or yearnings cause an individual anxiety, the individual wishes to reduce that anxiety. To do that, the individual’s unconscious mind uses ego defense mechanisms, unconscious protective behaviors that aim to reduce anxiety. The ego, usually conscious, resorts to unconscious strivings to protect the ego from being overwhelmed by anxiety. When we use defense mechanisms, we are unaware that we are using them. Further, they operate in various ways that distort reality. According to Freud, we all use ego defense mechanisms.

While everyone uses defense mechanisms, Freud believed their overuse may be problematic. For example, let’s say Joe Smith is a high school football player. Deep down, Joe feels sexually attracted to males. His conscious belief is that being gay is immoral and that if he were gay, his family would disown him and he would be ostracized by his peers. Therefore, there is a conflict between his conscious beliefs (being gay is wrong and will result in being ostracized) and his unconscious urges (attraction to males). The idea that he might be gay causes Joe to have feelings of anxiety. How can he decrease his anxiety? Joe may find himself acting very “macho,” making gay jokes, and picking on a school peer who is gay. This way, Joe’s unconscious impulses are further submerged.

Video 2. Defense Mechanisms explained.

There are several different types of defense mechanisms. For instance, in repression, anxiety-causing memories from consciousness are blocked. As an analogy, let’s say your car is making a strange noise, but because you do not have the money to fix it, you just turn up the radio so that you no longer hear the noise. Eventually, you forget about it. Similarly, if a memory is too overwhelming to deal with in the human psyche, it might be repressed and thus removed from conscious awareness (Freud, 1920). This repressed memory might cause symptoms in other areas.

Another defense mechanism is reaction formation, in which someone expresses feelings, thoughts, and behaviors opposite to their inclinations. In the above example, Joe made fun of a homosexual peer while himself being attracted to males. In regression, an individual acts much younger than their age. For example, a four-year-old child who resents the arrival of a newborn sibling may act like a baby and revert to drinking out of a bottle. In projection, a person refuses to acknowledge her own unconscious feelings and instead sees those feelings in someone else. Other defense mechanisms include rationalization, displacement, and sublimation.

Stages of Psychosexual Development

Freud believed that personality develops during early childhood. Childhood experiences shape our personalities and behavior as adults. He asserted that we develop via a series of stages during childhood. Each of us must pass through these childhood stages, and if we do not have the proper nurturing and parenting during a stage, we will be stuck or fixated in that stage, even as adults.

In each psychosexual stage of development, the child’s pleasure-seeking urges, coming from the id, are focused on a different area of the body, called an erogenous zone. The stages are oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital (Table 1). The human development chapter provides more details about these developmental stages.

| Stage | Age (years) | Erogenous Zone | Major Conflict | Adult Fixation Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | 0–1 | Mouth | Weaning off breast or bottle | Smoking, overeating |

| Anal | 1–3 | Anus | Toilet training | Neatness, messiness |

| Phallic | 3–6 | Genitals | Oedipus/Electra complex | Vanity, overambition |

| Latency | 6–12 | None | None | None |

| Genital | 12+ | Genitals | None | None |

Freud’s Theories Today

Empirical research assessing psychodynamic concepts has produced mixed results, with some concepts receiving good empirical support and others not faring as well. For example, the notion that we express strong sexual feelings from a very early age, as the psychosexual stage model suggests, has not held up to empirical scrutiny. On the other hand, the idea that there are dependent, control-oriented, and competitive personality types—an idea also derived from the psychosexual stage model—does seem useful.

Many ideas from the psychodynamic perspective have been studied empirically. Luborsky and Barrett (2006) reviewed much of this research; Bornstein (2005), Gerber (2007), and Huprich (2009) provide other useful reviews. Let’s look at three psychodynamic hypotheses that have received strong empirical support.

- As the psychodynamic perspective predicts, unconscious processes influence our behavior. We perceive and process much more information than we realize, and much of our behavior is shaped by feelings and motives of which we are, at best, only partially aware (Bornstein, 2009, 2010). Evidence for the importance of unconscious influences is so compelling that it has become a central element of contemporary cognitive and social psychology (Robinson & Gordon, 2011).

- We all use ego defenses, which help determine our psychological adjustment and physical health. People really differ in the degree that they rely on different ego defenses—so much so that researchers now study each person’s “defense style” (the unique constellation of defenses we use). It turns out that certain defenses are more adaptive than others: Rationalization and sublimation are healthier (psychologically speaking) than repression and reaction formation (Cramer, 2006). Denial is, quite literally, bad for your health because people who use denial tend to ignore symptoms of illness until it’s too late (Bond, 2004).

- Mental representations of self and others serve as blueprints for later relationships. Dozens of studies have shown that mental images of our parents and other significant figures really do shape our expectations for later friendships and romantic relationships. The idea that you choose a romantic partner who resembles mom or dad is a myth, but it’s true that you expect to be treated by others as you were treated by your parents early in life (Silverstein, 2007; Wachtel, 1997).

Think It Over

- What are some examples of defense mechanisms that you have used yourself or have witnessed others using?

Glossary

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- What is Personality?. Authored by: OpenStax College. Retrieved from: http://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:YJjSZ1SS@5/What-Is-Personality#Figure_11_01_FourTemper. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11629/latest/.

- Freud's Theories Today. Authored by: Robert Bornstein . Provided by: Adelphi University. Retrieved from: http://nobaproject.com/modules/the-psychodynamic-perspective. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Rorschach & Freudians: Crash Course Psychology #21. Provided by: CrashCourse. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mUELAiHbCxc&feature=youtu.be&list=PL8dPuuaLjXtOPRKzVLY0jJY-uHOH9KVU6. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License