52 Motivation

Motivation to engage in a given behavior can come from internal and/or external factors. There are multiple theories have been put forward regarding motivation—biologically oriented theories that say the need to maintain bodily homeostasis motivates behavior, Bandura’s idea that our sense of self-efficacy motivates behavior, and others that focus on social aspects of motivation. In this section, you’ll learn about these theories as well as the famous work of Abraham Maslow and his hierarchy of needs.

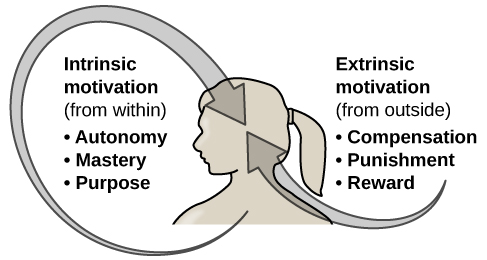

Why do we do the things we do? What motivations underlie our behaviors? Motivation describes the wants or needs that direct behavior toward a goal. In addition to biological motives, motivations can be intrinsic (arising from internal factors) or extrinsic (arising from external factors) (Figure 1). Intrinsically motivated behaviors are performed because of the sense of personal satisfaction that they bring, while extrinsically motivated behaviors are performed in order to receive something from others.

Think about why you are currently in college. Are you here because you enjoy learning and want to pursue an education to make yourself a more well-rounded individual? If so, then you are intrinsically motivated. However, if you are here because you want to get a college degree to make yourself more marketable for a high-paying career or to satisfy the demands of your parents, then your motivation is more extrinsic in nature.

In reality, our motivations are often a mix of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, but the nature of these factors might change over time (often in ways that seem counter-intuitive). There is an old adage: “Choose a job that you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life,” meaning that if you enjoy your occupation, work doesn’t seem like . . . well, work. Research suggests this isn’t necessarily the case (Daniel & Esser, 1980; Deci, 1972; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). According to this research, receiving some extrinsic reinforcement (i.e., getting paid) for engaging in behaviors that we enjoy leads to those behaviors being thought of as work no longer providing that same enjoyment. As a result, we might spend less time engaging in these reclassified behaviors in the absence of any extrinsic reinforcement. For example, Odessa loves baking, so in her free time, she bakes for fun. Oftentimes, after stocking shelves at her grocery store job, she often whips up pastries in the evenings because she enjoys baking. When a coworker in the store’s bakery department leaves his job, Odessa applies for his position and gets transferred to the bakery department. Although she enjoys what she does in her new job, after a few months, she no longer has much desire to concoct tasty treats in her free time. Baking has become work in a way that changes her motivation to do it (Figure 2). Odessa has experienced the overjustification effect—intrinsic motivation is diminished when extrinsic motivation is given. This can lead to extinguishing intrinsic motivation and creating a dependence on extrinsic rewards for continued performance (Deci et al., 1999).

Other studies suggest that intrinsic motivation may not be so vulnerable to the effects of extrinsic reinforcements, and in fact, reinforcements such as verbal praise might increase intrinsic motivation (Arnold, 1976; Cameron & Pierce, 1994). In that case, Odessa’s motivation to bake in her free time might remain high if, for example, customers regularly compliment her baking or cake decorating skills.

These apparent discrepancies in the researchers’ findings may be understood by considering several factors. For one, physical reinforcement (such as money) and verbal reinforcement (such as praise) may affect an individual differently. In fact, tangible rewards (i.e., money) tend to have more negative effects on intrinsic motivation than do intangible rewards (i.e., praise). Furthermore, an individual’s expectation of the extrinsic motivator is crucial: If the person expects to receive an extrinsic reward, then the intrinsic motivation for the task tends to be reduced. If there is no such expectation, and the extrinsic motivation is presented as a surprise, then the intrinsic motivation for the task tends to persist (Deci et al., 1999).

In educational settings, students are more likely to experience intrinsic motivation to learn when they feel a sense of belonging and respect in the classroom. This internalization can be enhanced if the evaluative aspects of the classroom are de-emphasized and if students feel that they exercise some control over the learning environment. Furthermore, providing students with challenging yet doable activities and a rationale for engaging in various learning activities can enhance intrinsic motivation for those tasks (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). Consider Hakim, a first-year law student taking two courses this semester: Family Law and Criminal Law. The Family Law professor has a rather intimidating classroom: He likes to put students on the spot with tough questions, which often leaves students feeling belittled or embarrassed. Grades are based exclusively on quizzes and exams, and the instructor posts the results of each test on the classroom door. In contrast, the Criminal Law professor facilitates classroom discussions and respectful debates in small groups. Most of the course grade is not exam-based but centers on a student-designed research project on a crime issue of the student’s choice. Research suggests that Hakim will be less intrinsically motivated in his Family Law course, where students are intimidated in the classroom setting, and there is an emphasis on teacher-driven evaluations. Hakim is likely to experience a higher level of intrinsic motivation in his Criminal Law course, where the class setting encourages inclusive collaboration and a respect for ideas, and where students have more influence over their learning activities.

Theories about Motivation

Another early theory of motivation proposed that the maintenance of homeostasis is particularly important in directing behavior. You may recall from your earlier reading that homeostasis is the tendency to maintain a balance, or optimal level, within a biological system. In a body system, a control center (which is often part of the brain) receives input from receptors (which are often complexes of neurons). The control center directs effectors (which may be other neurons) to correct any imbalance detected by the control center.

According to the drive theory of motivation, deviations from homeostasis create physiological needs. These needs result in psychological drive states that direct behavior to meet the need and, ultimately, bring the system back to homeostasis. For example, if it’s been a while since you ate, your blood sugar levels will drop below normal. This low blood sugar will induce a physiological need and a corresponding drive state (i.e., hunger) that will direct you to seek out and consume food (Figure 4). Eating will eliminate the hunger, and, ultimately, your blood sugar levels will return to normal. Interestingly, drive theory also emphasizes the role that habits play in the type of behavioral response in which we engage. A habit is a pattern of behavior in which we regularly engage. Once we have engaged in a behavior that successfully reduces a drive, we are more likely to engage in that behavior whenever faced with that drive in the future (Graham & Weiner, 1996).

Extensions of drive theory take into account levels of arousal as potential motivators. Just as drive theory aims to return the body to homeostasis, arousal theory aims to find the optimal level of arousal. If we are under-aroused, we become bored and will seek out some sort of stimulation. On the other hand, if we are over-aroused, we will engage in behaviors to reduce our arousal (Berlyne, 1960). Most students have experienced this need to maintain optimal levels of arousal over the course of their academic careers. Think about how much stress students experience toward the end of the semester. They feel overwhelmed with seemingly endless exams, papers, and major assignments that must be completed on time. They probably yearn for the rest and relaxation that awaits them over the extended break. However, once they finish the semester, it doesn’t take too long before they begin to feel bored. Generally, by the time the next semester is beginning in the fall, many students are quite happy to return to school. This is an example of how arousal theory works.

So what is the optimal level of arousal? What level leads to the best performance? Research shows that moderate arousal is generally best; when arousal is very high or very low, performance tends to suffer (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). Think of your arousal level regarding taking an exam for this class. If your level is very low, such as boredom and apathy, your performance will likely suffer. Similarly, a very high level, such as extreme anxiety, can be paralyzing and hinder performance. Consider the example of a softball team facing a tournament. They are favored to win their first game by a large margin, so they go into the game with a lower level of arousal and get beat by a less skilled team.

But optimal arousal level is more complex than a simple answer that the middle level is always best. Researchers Robert Yerkes (pronounced “Yerk-EES”) and John Dodson discovered that the optimal arousal level depends on the complexity and difficulty of the task to be performed (Figure 6). This relationship is known as Yerkes-Dodson law, which holds that a simple task is performed best when arousal levels are relatively high and complex tasks are best performed when arousal levels are lower.

Self-efficacy and Social Motives

Self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in her own capability to complete a task, which may include a previous successful completion of the exact task or a similar task. Albert Bandura (1994) theorized that an individual’s sense of self-efficacy is pivotal in motivating behavior. Bandura argues that motivation derives from expectations about the consequences of our behaviors, and ultimately, it is the appreciation of our capacity to engage in a given behavior that will determine what we do and the future goals we set for ourselves. For example, if you sincerely believe in your ability to achieve at the highest level, you are more likely to take on challenging tasks and not let setbacks dissuade you from seeing the task through to the end.

A number of theorists have focused their research on understanding social motives (McAdams & Constantian, 1983; McClelland & Liberman, 1949; Murray et al., 1938). Among the motives, they describe the need for achievement, affiliation, and intimacy. It is the need for achievement that drives accomplishment and performance. The need for affiliation encourages positive interactions with others, and the need for intimacy causes us to seek deep, meaningful relationships. Henry Murray et al. (1938) categorized these needs into domains. For example, the need for achievement and recognition falls under the domain of ambition. Dominance and aggression were recognized as needs under the domain of human power, and play was a recognized need in the domain of interpersonal affection.

Watch It

Watch this video from Dan Pink’s Ted talk on “The surprising truth about what motivates us.” Think about what things motivate you, and how you anticipate that you might respond to the types of incentives explained in the talk.

At the base of the pyramid are all of the physiological needs that are necessary for survival. These are followed by basic needs for security and safety, the need to be loved and to have a sense of belonging, and the need to have self-worth and confidence. The top tier of the pyramid is self-actualization, which is a need that essentially equates to achieving one’s full potential, and it can only be realized when needs lower on the pyramid have been met. To Maslow and humanistic theorists, self-actualization reflects the humanistic emphasis on positive aspects of human nature. Maslow suggested that this is an ongoing, life-long process and that only a small percentage of people actually achieve a self-actualized state (Francis & Kritsonis, 2006; Maslow, 1943).

According to Maslow (1943), one must satisfy lower-level needs before addressing those needs that occur higher in the pyramid. So, for example, if someone is struggling to find enough food to meet his nutritional requirements, it is quite unlikely that he would spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about whether others viewed him as a good person or not. Instead, all of his energies would be geared toward finding something to eat. However, it should be pointed out that Maslow’s theory has been criticized for its subjective nature and its inability to account for phenomena that occur in the real world (Leonard, 1982). Other research has more recently addressed that late in life, Maslow proposed a self-transcendence level above self-actualization—to represent striving for meaning and purpose beyond the concerns of oneself (Koltko-Rivera, 2006). For example, people sometimes make self-sacrifices in order to make a political statement or in an attempt to improve the conditions of others. Mohandas K. Gandhi, a world-renowned advocate for independence through nonviolent protest, went on hunger strikes on several occasions to protest a particular situation. People may starve themselves or otherwise, put themselves in danger displaying higher-level motives beyond their own needs.

Link to Learning

Check out this interactive exercise that illustrates some of the important concepts in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Glossary

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Psychology in Real Life: Growth Mindsets. Authored by: Patrick Carroll for Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Motivation. Authored by: OpenStax College. Retrieved from: http://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:MLADqXMi@5/Motivation. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/4abf04bf-93a0-45c3-9cbc-2cefd46e68cc@5.48

- climbing picture. Provided by: Pixabay. Retrieved from: https://www.pexels.com/photo/achievement-action-adventure-backlit-209209/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- picture of teacher with students. Authored by: Army Medicine. Provided by: Flickr. Retrieved from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/armymedicine/13584535514. License: CC BY: Attribution

- RSA ANIMATE: Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Authored by: Dan Pink. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6XAPnuFjJc. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Math student gets help from teacher. Authored by: Sue Sapp. Provided by: U.S. Air Force. Retrieved from: http://www.robins.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2000659561/. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright