53 Goal Orientation Theory

Goal setting is a key motivational process (Locke & Latham, 1984). Goals are the outcomes that a person is trying to accomplish. People engage in activities that are believed to lead to goal attainment. As individuals pursue multiple goals, such as academic and social goals, goal choice and the level at which they commit to attaining the goals influence their motivation (Locke & Latham, 2006; Wentzel, 2000).

Besides goal content (i.e., what a person wants to achieve), the reason that a person tries to achieve a certain goal also significantly influences performance. Goal orientations refer to the reasons or purposes for engaging in a goal and explain individuals’ different ways of approaching and responding to achievement situations (Ames & Archer, 1988; Meece, Anderman, & Anderman, 2006). Mastery and performance goals are the two most basic goal orientations (Ames & Archer, 1988). A mastery goal orientation is focused on mastering new skills, gaining increased understanding, and improving competence (Ames & Archer, 1988). Students adopting mastery goals define success in terms of improvement and learning. In contrast, a performance goal orientation focuses on doing better than others and demonstrating competence, for example, by striving to best others, using social comparative standards to judge their abilities while seeking favorable judgment from others (Dweck & Leggett, 1988).

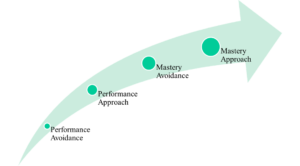

In addition to the basic distinction between mastery and performance goals, performance goal orientations have been further differentiated into performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals (Elliot & Church, 1997; Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996). Performance-approach goals represent individuals motivated to outperform others and demonstrate their superiority, whereas a performance-avoidance goal orientation refers to those motivated to avoid negative judgments and appear inferior to others. Incorporating the same approach and avoidance distinction, some researchers have further distinguished mastery-approach and mastery-avoidance goals (Elliot & McGregor, 2001). Mastery-approach goals are related to improving knowledge, skills, and learning. In contrast, mastery-avoidance goals focus on avoiding misunderstanding or failing to master a task. For instance, athletes concerned about falling short of their past performances reflect a mastery-avoidance goal. Despite the confirmatory factor analyses of the 22-goal framework (Elliot & McGregor, 2001; see Table 1), the mastery-avoidance construct remains controversial and is, in fact, the least accepted construct in the field.

Table 1. Model of goal orientations

| Mastery Goal | Performance Goal | |

| Approach Focus | Focus on mastery of learning

|

Focus on outperforming others

|

| Avoidance Focus | Focus on avoiding not mastering task

|

Focus on avoiding failure

|

Studies typically report that mastery-approach goals are associated with positive achievement outcomes such as high levels of effort, interest in the task, and use of deep learning strategies (e.g., Greene, Miller, Crowson, Duke, & Akey, 2004; Harackiewicz, Barron, Pintrich, Elliot, & Thrash, 2002; Wolters, 2004). On the other hand, research on performance-avoidance goals has consistently reported that these goals induced detrimental effects, such as poor persistence, high anxiety, use of superficial strategies, and low achievement (Linnenbrink, 2005; Urdan, 2004; Wolters, 2003, 2004). With regard to performance-approach goals, the data have yielded a mix of outcomes. Some studies have reported modest positive relations between performance-approach goals and achievement (Linnenbrink-Garcia, Tyson, & Patall, 2008). Others have found maladaptive outcomes such as poor strategy use and test anxiety (Keys, Conley, Duncan, & Domina, 2012; Elliot & McGregor, 2001; Middleton & Midgley, 1997). Taken together, these findings suggest that students who adopt performance-approach goals demonstrate high levels of achievement but experience negative emotionality, such as test anxiety. Mastery-avoidance goals are the least studied goal orientation thus far. However, some studies have found mastery-avoidance to be a positive predictor of anxiety and a negative predictor of performance (Howell & Watson, 2007; Hulleman, Schrager, Bodmann, & Harackiewicz, 2010).

Figure 1. The likelihood of goal success is influenced by the goal orientation. Mastery-approach goals are most likely to be successful, and performance-avoidance goals are least likely.

Video 1. Goal Orientation Theory explains the four goal orientations and their implications.

Goals that Contribute to Achievement

As you might imagine, mastery, performance, and performance-avoidance goals often are not experienced in pure form but in combinations. If you play the clarinet in the school band, you might want to improve your technique simply because you enjoy playing as well as possible—essentially, a mastery orientation. But you might also want to look talented in classmates’ eyes—a performance orientation. Another part of what you may wish, at least privately, is to avoid looking like a complete failure at playing the clarinet. One of these motives may predominate over the others, but they all may be present.

Mastery goals tend to be associated with the enjoyment of learning the material at hand and, in this sense, represent an outcome that teachers often seek for students. By definition, therefore, they are a form of intrinsic motivation. Mastery goals are better than performance goals at sustaining students’ interest in a subject. In one review of research about learning goals, for example, students with primarily mastery orientations toward a course they were taking not only tended to express greater interest in the course but also continued to express interest well beyond the official end of the course and to enroll in further courses in the same subject (Harackiewicz et al., 2002; Wolters, 2004).

On the other hand, performance goals imply extrinsic motivation and tend to show the mixed effects of this orientation. A positive effect is that students with a performance orientation tend to get higher grades than those who primarily express mastery orientation. The advantage in grades occurs both in the short term (with individual assignments) and in the long term (with an overall grade point average when graduating). However, there is evidence that performance-oriented students do not actually learn the material as deeply or permanently as more mastery-oriented students (Midgley, Kaplan, & Middleton, 2001). A possible reason is that performance measures—such as test scores—often reward relatively shallow memorization of information, guiding performance-oriented students away from processing the information thoughtfully or deeply. Another possible reason is that a performance orientation, by focusing on gaining recognition as the best among peers, encourages competition among peers. Giving and receiving help from classmates is thus not in the self-interest of a performance-oriented student, and the resulting isolation limits the student’s learning.

Candela Citations

- Goal Orientation Theory. Authored by: Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose. Provided by: Hudson Valley Community College. Retrieved from: https://edpsych.pressbooks.sunycreate.cloud/chapter/goal-orientation-theory/#:~:text=Goal%20orientations%20refer%20to%20the,%2C%20%26%20Anderman%2C%202006).. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike